The backdrop:

Chetan Agrawal (name changed) works as a Director, Operations at a hospitality-tech company. At the onset of the pandemic, he really enjoyed working from home and slowly started putting in much more work. Eventually, he became a slave of notifications and lost sleep. Over time, he was expected to work over and above normal hours and this made him anxious. He then had to consult a psychiatrist and was put on sleeping pills for about a month.

This pattern of sleeplessness continued and despite his upcoming review, he has taken a sabbatical from his company. Says Agrawal, “multiple work and personal issues have bothered me and I put a lot of undue pressure on myself.” My company has been cooperative with my request, since I have even worked the weekends. Agrawal is going for a 10 day Vipassana course and has already started changing his daily routine to cope (the good part is, he is off sleeping pills now).

Neha Verma (name changed) pivoted her career during the pandemic. She was bang in the middle of her MBA when it struck and she had to take up 6 internships. She lost one of them due to the pandemic and worked doubly hard (almost 18 hours a day) during the next - she really wanted to be placed in the consultancy that gave her the unpaid internship. She got great reviews that did not translate into a job, but left her burned out. So much so that while she had above average ratings in her next two internships and landed a full time job in May 2021, she now feels disconnected from colleagues and says her new company has ‘normalised burnout’. The company culture is aggressive, they are constantly chasing targets and since the company is making great strides, they celebrate ‘hustling.’

Rahul Jain (name changed) worked for a food delivery startup until recently. The pandemic was very strenuous for him and his team. It completely changed the way they conducted business affairs, and they had to work with multiple Government directives during lockdowns etc. The company was proactive and came up with several initiatives to mitigate pressure. Jain shares, "I had Covid-19 during the second wave and my personal health is now compromised. I was in perfect shape and now I feel I have aged ten years. I am unable to workout the way I used to. That is having a lot of repercussions on me.”

All the instances related above are true and you must have come across many such instances as well. We spoke to these people (and many more) in confidence to understand pandemic work behaviour and what we found was disheartening. In the cases here or the many others we spoke to, we saw a wide chasm. Working from home, made people work a lot harder and while well meaning organisations came up with many ‘work-life-balance’ policies, most of them were either knee-jerk, reactive or ‘just done to check off a box.’ Making sweeping statements is not our intent, however, let us assess this situation by referring to its historical journey.

The history of workplace wellness:

Workplace wellbeing can be dated back to the late-1800s. William McPeck, Wellbeing Strategist and Systems Integrator has divided this evolution into phases and it may be worth calling them out to understand how companies have defined employee health and wellbeing over the years.

- The social and recreational phase: The earliest reported incidence of wellness being practised in the workplace dates back to 1897 at the Pullman Company near Chicago, Illinois. In an effort to accommodate their labour needs and the needs of rural individuals coming to the city in search of work, many companies during this period created company towns, or communities/neighbourhoods within larger municipalities. As part of their company town, The Pullman Company created an employee athletic association to complement their company-provided housing, stores and schools. Other companies at the time, including National Cash Register, Sears, Roebuck & Company, and Hershey Foods also created employee recreational initiatives.

- The fitness phase: In the late 1950's, the focus of the worksite wellness began to shift from social and recreation to fitness. PepsiCo began their renowned employee fitness program in the late 1950's. PepsiCo was followed in the 1960's by Sentry Insurance, Rockwell International, Xerox Corporation, American Can and NASA launching employee fitness programs.

- The medical phase: With the emphasis on cardiovascular disease, executive health emerged as a program focus. The combination of increased attention to cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases, along with escalating employer related healthcare costs resulted in the 1980’s worksite wellness programs becoming more focused on and aligned with the pathogenesis model of medicine, or the medical model. This resulted in increased attention being given to employee health promotion, along with an emphasis on health risk reduction and individual responsibility for health. As a result, health education, health risk assessments, biometric screenings and individual behaviour change initiatives became the core programming found within worksite wellness programs. In order to substantiate their impact on employer healthcare costs, ROI (return-on-investment) measurement became the most common way of evaluating worksite wellness program success.

- The fusion phase: As the 21st century loomed on the horizon, population health management entered the workplace and available resources became increasingly tighter. Researchers have also been able to establish that individual health is the result of a combination of determinants and not just individual lifestyle. This has resulted in an increasing recognition that there needs to be better integration across the various silos of employee benefits delivery and with core business strategies and practices as well.

All of this was before the pandemic. To say the pandemic caused a stir, is to put it lightly.

Pandemic-productivity-paradox:

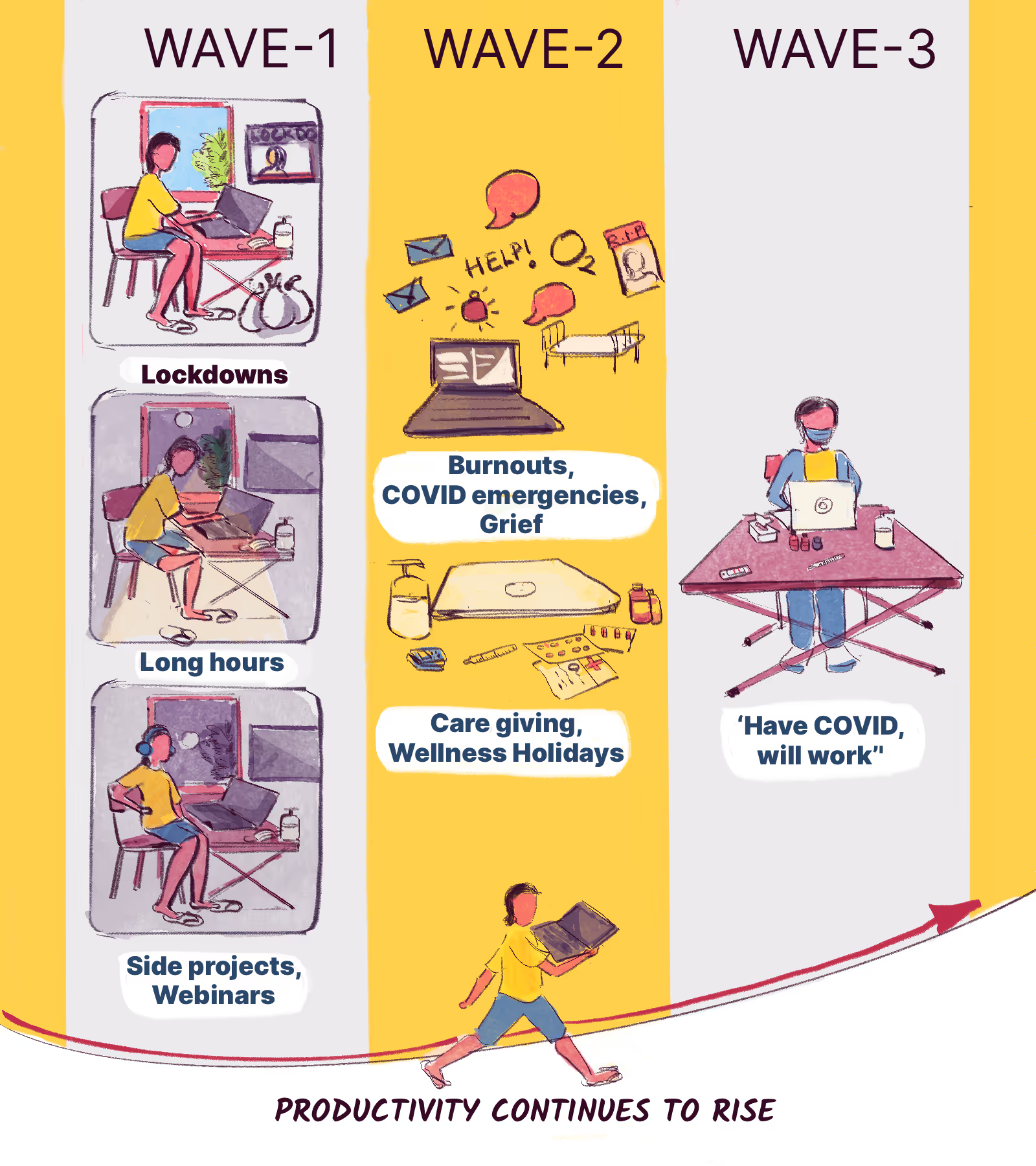

Two years into the pandemic have put people 20 years back with respect to their physical health and mental wellbeing. A 2020 report by Oracle and Workplace Intelligence found that 2020 was the most stressful year people in our generation have suffered during their work lives. Conversely, the world’s output per hour worked surged by 4.9 per cent in 2020, more than double the long-term average annual rate of 2.4 per cent registered between 2005 and 2019. This is called the productivity-paradox. Here is a rough timeline of how work panned out for many employees and organisations during the pandemic.

Wave 1

- Work 16-18 hours a day (since there is nothing else to do)

- Engage in side projects and webinars

- Organisations celebrate peak productivity

Wave 2

- Feeling burned out, yet working hard

- Covid-19 situation out of control; organisations start giving Covid-19 and caregiver’s leave, helping employees find hospital beds and oxygen cylinders

- Grief and anxiety strike, yet hard work continues

- Organisations start creating policies like, ‘no meeting Wednesdays’, ‘mental health leaves’, ‘self-care breaks’

- Still celebrate productivity and the despite the above policies, continue same old work practices

Wave 3:

- Have omicron, will work

- Organisations - let’s work from home (but keep working)

While it all looks great and we have been celebrating the rise in productivity and a treadmill-like ‘always-on’ work culture, does something strike you as odd?

The Sin of Good Intent

If you follow discussions around climate change and marketing stunts pulled off by companies under the pretext of climate change, you are aware of the term ‘greenwashing*’. It simply means when a company purports to be environmentally conscious, but is not making any sustainability efforts. Companies can greenwash even if they have good intent. Extrapolate this to the productivity-paradox and you will see the parallels. Companies talk about ‘mental wellness’, ‘burnout’, ‘resilience’, ‘empathy’, ‘employee wellbeing’ and mean anything but that. Are we being blatant? Well, how many companies do you know mean it when they say ‘no meeting Wednesdays’, ‘no emails post 6:00 p.m',’ ‘no working over weekends’ and so on? See what we are saying?

(*Read more about the sin of good intent in this post by Tanmoy Goswami - Sanity by Tanmoy).

Similarly, workplace wellness is a good-to-have pitch to attract the best candidates, it is also the product of the INR 21.35 billion (by 2025) corporate wellness industry. However, it is still an aspect many companies think half-heartedly about and there is a gap between policies and practice. The biggest reason is because companies do not ask their employees about what works for them. It is not a two-way dialogue. The second reason is because we still celebrate the hustle culture, without paying much attention to what it does to our health. The third could possibly be because it is hard to measure and quantify.

Walking-the-talk.

We must confess, as we write this, everything is not doom and gloom. There are companies that are getting it right and are genuinely incorporating practices that enhance employee wellbeing. Many employees we spoke to did acknowledge their company's efforts in curbing the always-on culture. Many people we spoke to have also used this period to completely reset their lifestyle and prioritise their health. What we are saying is, that these efforts require continuous follow-through and strict governance to last and make an impact. Since we like questioning the status quo at Humanise by Plum, let us highlight practices that resonate with us.

Is productivity only the number of hours or days worked?

Nandini Vishwanath a venture capitalist with early stage fund, Antler works with founders day in and out to help them build lasting enterprises. She believes it is important for organisations to play a part in employee wellbeing and says, "we are a generation that migrates for work - a lot of our socialising is with our colleagues or for work. When we are investing a lot of ourselves in our work, our employers should be thinking of our wellbeing too. However, the lines are blurred. For example: do you want your colleague/ boss to know about your infertility treatments?"

First, it is important to define which aspects of wellness should the office focus on and the second aspect is how should both the organisation and the employee be incentivised (since this is still a grey area with no set measurables). Nandini suggests a model where productivity is a function of output and impact and not so much about the number of days worked or the hours put in. She further adds, "Just as an executive coach suggests mental models/ frameworks to deal with certain decisions, similarly, organisations should think of productivity as a framework and measure aspects like: speed of decision making, follow throughs, execution and other aspects that are important for a company’s growth."

On the question of who exactly within the organisation is responsible for wellbeing, the consensus is everyone. Our team, managers and leaders equally are and while the decision making vests in a few functions, we are all a unit at work and have to have equal say/ or at least the right to express our opinion. Just thinking of physical health and equating it with productivity is not enough. Atharva Kharbade, works at Ultrahuman and manages growth. He shares how as a 20-something year old, he has suffered from isolation and anxiety related mental health issues and believes that companies should be responsible in sponsoring therapy costs (if that helps employees present their full selves to work). He says, "organisations have a role to play in mental health and wellbeing especially of their younger employees. With return to work (after two years of isolation), even extroverts are socially anxious".

Though, if one has to measure productivity in a complex situation like this, there is no ‘interesting-lever’ for any organisation to want to get involved. Hence, many mental health initiatives are band-aid like*. However, if done right, without wanting to measure productivity, but for the good of all, it is a powerful initiative to reimburse employees for therapy or equally care for their mental well-being.

* we will cover this issue separately

Are policies enough, why not think of measurable interventions?

Plum conducted a survey among its employees to understand how organisations can involve themselves in employee wellbeing and found - 1) habit forming 2) lack of time and 3) lack of community support, to be the top three reasons it is hard for workplace wellbeing to progress beyond ‘just policies’. Equipped with the findings of this survey, the company is for the first time, introducing ‘quarterly wellbeing OKRs’ (objectives and key results) for all employees. These OKRs will be set by the employees, tracked and rewarded based on consistency and impact. Saurabh Arora, Co-founder, CTO and Head of Wellness at Plum has identified a three part mechanism to make workplace wellbeing easier to execute:

- Calling out imbalanced time structures: Saurabh says, “WFH has stolen away our time structure and boundaries. Further, if Managers work 24*7, it is expected that the rest of the team does the same. Having worked across continents like Europe and Australia, I can safely say we need to communicate our boundaries better and also not assume that work is 24*7.” The key message here is to over communicate and never leave time structures open to interpretation. Safeguarding me-time is equally important in a fast-paced work environment.

- Training Managers: Managers play an important role not only in employee performance, but their overall lives and hence it is imperative Managers are trained and better equipped to enable their team’s wellbeing. Large organisations have to create systems to make people better Managers and that is important if workplace wellness is to be institutionalised. Especially in remote work, people work only in clusters of their own teams and this makes the Manager’s job both important and harder; hence Managers have to be equipped with better training on handling the wellbeing of distributed teams.

- Building micro communities: At Plum, there are micro communities for sports (currently football, will be expanding to other sports as well), the culture club (for movie screenings), the book club, and the financial and overall growth community. The idea is to provide systems and support to people to enable them to become better versions of themselves. That could also mean L&D and identifying the best knowledge courses from across the globe; for example: leadership coaching, support structures for Managers, etc. that make people connect deeply with themselves.

Overall, workplace wellbeing is not really a policy, but attitude and interventions. Remember, we are people working with people at the end of the day. Therefore, even if we learn on the way and fail (many times), what we should not be blamed for is the lack of trying or genuine intent.

.svg)

.png)

.webp)

%20(1).jpg)

.png)

.svg)