Having a baby doesn’t come cheap. Giving birth can cost anywhere between INR 30,000* (that’s the average starting price of a normal delivery in an urban city) and INR 80,000 (in an upscale private hospital). In Bangalore (comparable to other urban cities, metros) the average cost hovers around INR 55,000. But, averages often don’t tell the whole story. There are caveats to these numbers.

- The first is that it’s a normal delivery (that is to say, a vaginal birth) as opposed to a caesarean section (C-section). But normal deliveries are quickly becoming the exception. In many states in India, more than half of all child births in private hospitals are C-sections. *See below for data

- The second caveat is that there are no health complications in either the mother or the new-born. As we explain later, complications in births are on the rise too.

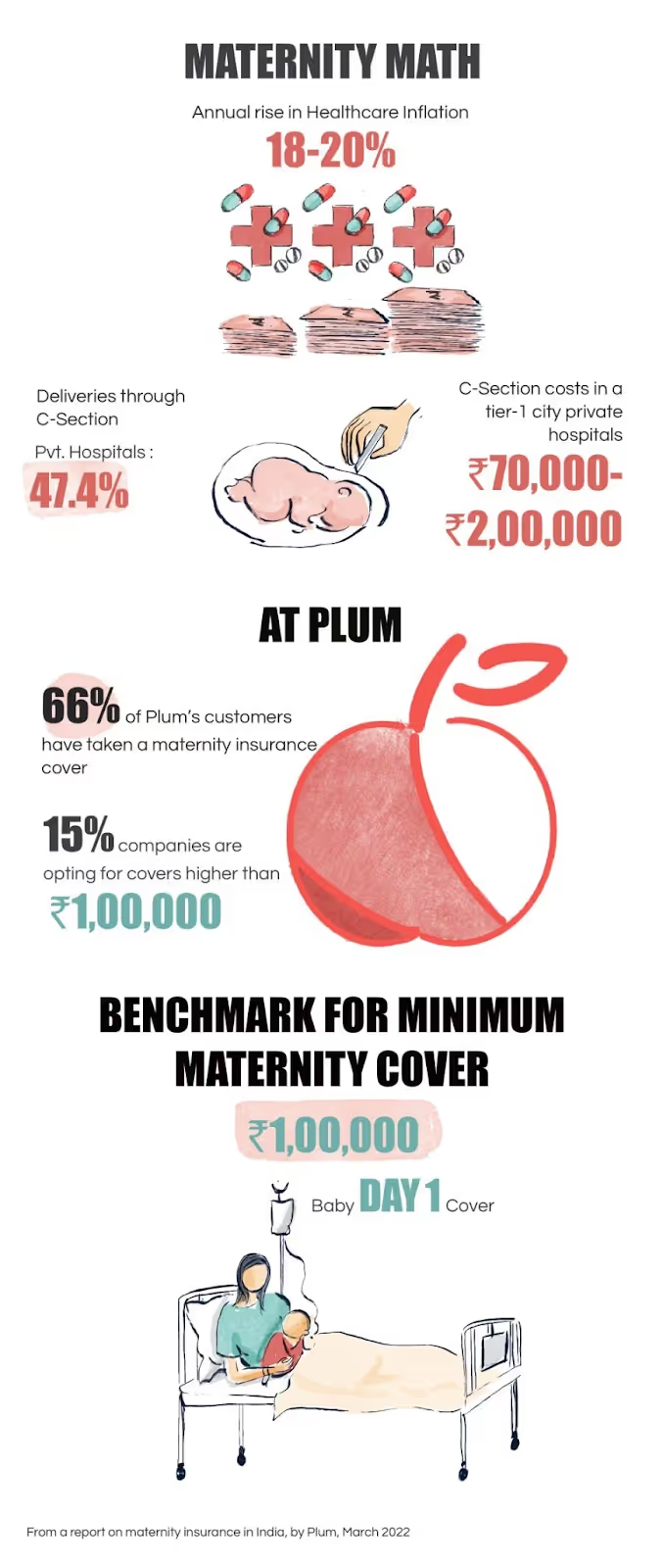

The rising costs of healthcare in India

In early 2019, it was found that even while food inflation and consumer price inflation was down, rural healthcare inflation was up. The urban scenario is not too far behind. Healthcare inflation in India is rising at 18-20% annually (rate of change). So, while having a baby ought to be an exciting part of a couple’s life together, the road may be fraught with financial worry. While maternity cover doesn’t seek to cover the costs of raising babies, it must at the very least cover the entire cost of giving birth in most cases. In the western world, there are stories of women in the midst of excruciating labour pain wondering out loud if the hospital would charge them for an extra epidural. Here in India, the grim reality of medical inflation is unlikely to cool anytime soon.

Other Challenges

- Standalone policies for maternity are non-existent: In India, you’d be hard pressed to find maternity insurance as standalone retail policies. This is because of the risks involved for insurance companies. Their rationale is that families planning a baby would undoubtedly purchase a policy, and the probability of a claim would be a 100%. In the world of insurance, this is called ‘anti-selection’. Maternity covers are easily available as a part of a base health insurance policy. These maternity policies can also include antenatal and postnatal expenses and a cover for the new-born as well.

- Baby Day One Cover: Another problem is that in retail health insurance, there’s a 90-day waiting period from the time of the child-birth. That is, a baby policy cover kicks in only on the 91st day of the new-born’s life. Before that period, insurance companies are usually not obligated to honour any claims from the customer. There is an option called ‘Baby Day One Cover’ that has great potential to solve this problem, but it’s only available in few, if any, retail health insurance policies. More on that later.

- Pregnancies can come with complications: In India 20-30% pregnancies are categorised as ‘high risk’ ones. Some of these high risk pregnancies can lead to complications during labour, and before or after as well.

- Infertility is on the rise: While the medical community in India has been unable to confirm it empirically (due to a lack of data), they feel that infertility is on the rise in India. As reported by The Print “ Indians’ sperm counts and egg reserves are dropping just like in the west”. Could a case be made for insurance to cover infertility here? And should insurers consider offering it in their group insurance policies as standard and without additional costs and restrictive terms? It is worth considering, especially since worldwide projections of fertility rates are plummeting. Infertility is a recognised medical condition and not a planned event in any case. (Global average fertility rates have dropped by half over the last 50 years alone)

- Retail policies come with waiting periods: A waiting period is when the insured cannot make any claims from the insurer. The duration differs from insurer to insurer and policy to policy. The typical waiting time for a policy with a maternity cover ranges from 9 months to 4 years.

There is some good-news, however. Group health insurance (GHI) policies are capable of covering every female employee (and spouses in the case of males) for maternity expenses from day 1 (they also cover infertility and any prenatal complications from the time the cover is made available to the employee). Additionally, they come with the option to cover newborns, which kicks in on the very day of their birth (called Baby Day One cover).

Maternity Maths

At Plum, over 66 percent of our customers have now adopted maternity covers. A majority of them cover expenses upto INR 50,000 for up to 2 children, and while that seems to meet the average urban city expense of child-birth, a closer look reveals a higher cover is not only desirable, but also a need that’s going unmet.

Average cost of child-birth (vaginal births) in tier 1 cities and metros in India at private hospitals. All figures in INR.

Bangalore - Avg : 55,000

Chennai - Avg: 53,000

Mumbai - Avg: 45,000

New Delhi - Avg: 51,000

Hyderabad - Avg: 45,000

Cost of C-sections in private hospitals can range between INR 70,000 and 2,00,000, depending on the level of complication. The Covid-19 pandemic caused these prices to rise even higher than was previously the case. In fact, hospitals usually refuse to reveal their C-section tariffs easily, requiring the mother to be present for physical examination before they can estimate costs. In many cases, expectant mothers are advised by the hospitals to be prepared for a bill that falls anywhere between INR 1,50,000- 2,00,000. Average figures sometimes can obfuscate more than they reveal. Here are two facts that can help understand the situation better:

- 21.5% of all deliveries in India are through C-section. In fact, in private hospitals this rate jumps up to 47.4%. This might be an indicator that C-sections are on the rise, maybe even by choice. In some private hospitals C-sections can cost upto INR 2,00,000, on average. This number does not always include post-op care and medication.

These averages don’t usually include the cost of hospital room rent, and they certainly don’t include the cost of antenatal tests, medicines or postnatal tests. In many Indian states the C-section rate is higher than the national average.

According to the WHO, C-sections have risen world-wide from 7% in the ‘90s to 21% of all child births in 2021. They estimate that by 2030, that rate would breach nearly half of all deliveries in many countries in the world. And when you consider the cost of C-section births being higher, a much clearer picture begins to emerge. Companies today are in a position to do better, much better. Within Plum’s own database, we see 15% companies (of those that have maternity benefits) taking up covers that range from INR 1,00,000 upwards for maternity. 100% of these companies opt for a Baby Day One cover (covering the baby from the day it is born).

Let’s set ourselves a higher-benchmark

Companies like Twilio, Mintmesh, Evenflow, Vonage, Ironsides are looking at maternity insurance more progressively, with covers higher than INR 50,000. Lifting the bar even higher are Sense Talent Labs and Sentieo, which offer their employees an INR 1,00,000 cover. Hardik Dedhia, Chief of Staff, Sentieo says “We’d known that a maternity cover less than a lakh was always going to be too low. But go back a couple of years or so, when we had to secure policies from agents and brokers, most insurers would refuse to give us a cover over fifty thousand. Today, we can get these covers, so there’s no reason not to do it. We don’t want to be penny-pinching on benefits. Women need better insurance covers and equitable leave policies for maternity.”

How should companies assess maternity benefits going forward?

Owing to healthcare inflation (that is higher in tier 1 cities), companies today should be assessing the ideal maternity cover based on: 1) rising maternity costs 2) evolving demographics and 3) need for greater inclusion. As a bare minimum, companies could look at a maternity cover as follows:

- Maternity - INR 1,00,000

- Baby Day One cover - From Day 1

- Pre and post natal expenses - INR 10,000

This is not about insurance alone. A discussion about maternity also throws up an opportunity for us to kindle other conversations on a related note; aspects of equity, social justice and progressive thinking around these ideas.

We would be remiss if we didn't address pregnancy discrimination, which is rampant but hard to prove. In 2015, Quartz India published an article headlined ‘Pregnancy remains a curse for working women in corporate India’. Most commonly, women who return from maternity leave are often made to feel guilty, and some find that their role has been filled in the intervening period. In some cases, they even return after leave to find they’ve been unofficially demoted. What makes this situation so slippery is that it’s hard to prove in labour courts, since companies often disguise their true intentions behind these misdeeds. While these scenarios may be rare in many people-first organisations, employers still need to take care that women who return to work are not left out of conversations and opportunities for career advancement.

Beyond Insurance

Going deeper, according to Advocate and Head of Growth at Ungendered Alisha Gonsalves, for workplaces to be truly considered equitable, they must also consider the following:

- Surrogacy and adoption leave policies and benefits: With infertility rising, and for parents who want to adopt, this would be the natural next step in thinking about maternity progressively. Recently the Himachal Pradesh high court passed a judgement in support of maternity leave for women who became mothers through surrogacy. But the fact still remains that many companies don’t have clear-cut policies, and that’s a sign that there is some catching up to be done.

- Same-sex partner maternity and leave benefits: Today, select insurance startups do offer health insurance to same-sex partners and live-in partners of members/employees covered under their group health policies (Plum does). But we’re still in a minority, and in general, most companies aren’t aware or are too slow to act, effectively dealing injustice to the LGBTQ community.

- Paternity leave and benefits: Few Indian companies are generous to new fathers, who normally don’t get much in terms of paid leave for paternity. Earlier this year, Twitter CEO Parag Agarwal tweeted he would take some time off after the birth of his child, and it had many Indians talking about paternity leave. A cultural shift is required, one in which we don’t expect only the mother to raise the baby, and recognise the equal role of the father as well.

As we write this, a Delhi High Court has ruled a significant judgement. It lays down that an ad-hoc employee should be entitled to maternity benefits (the same as a contractual employee) beyond the period of contract if the pregnancy occurred during the tenure of employment. In other words, as long as the baby is conceived during the period of employment, the mother should be covered by the employer's insurance policy. Google ‘maternity in the workplace’, and you'll realise that as a society, and even on a global level, we’ve got a lot of wrongs to right. In 2019, the percentage of women in India’s workforce fell to 20.3% ( from 26% in 2005). Even our neighbours Bangladesh and Sri Lanka do much better in this regard. We can infer that a lack of support for mothers is a significant factor in this, which is a symptom of the deeper problem of a patriarchal system.

When it comes to education, the women in our country are doing better than the men (i.e, growing at a faster rate), but as a culture, we seem to be making it harder for them to return to work after giving birth. Of course, it’s much worse in rural India, but there is still much friction that we need to eliminate even in our so-called progressive, technologically-forward urban companies. Companies have a responsibility towards this end, first by having clear-cut policies and then implementing them with passion and without prejudice.

.svg)

.avif)

.png)

.webp)

%20(1).jpg)

.png)

.svg)